The Men Behind the Curtain: The Council on Foreign Relations

A deep-dive into the history of America's premier globalist think tank

Never before in American history has it been so obvious that the individuals pulling the strings in this country are not our elected leaders.

Joe Biden’s presidency is possibly the best supporting evidence we’ll ever get that American presidents are little more than vestigial figureheads of an international deep-state establishment.

The idea that powerful men conspire behind the scenes is a concept as old as time, and far more than only “fringe conspiracy theorists” have warned about clandestine powers.

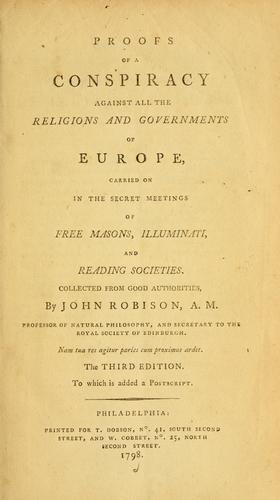

Our nation’s founder, George Washington, shortly before he died, read John Robison's book Proofs of a Conspiracy and immediately opined:

“It was not my intention to doubt that the doctrines of the Illuminati and principles of Jacobinism had not spread in the United States. On the contrary, no one is more truly satisfied of this fact than I am …”

John Robison, among many contemporary and future researchers, was adequately convinced that the machinations of a hidden group of Freemasons known as the Bavarian Illuminati had infiltrated the new world.

British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, as far back as 1856, told the House of Commons:

"It is useless to deny, because it is impossible to conceal, that a great part of Europe—the whole of Italy and France and a great portion of [then fragmented] Germany, to say nothing of other countries—is covered with a network of these secret societies … And what are their objects? They do not attempt to conceal them. They do not want constitutional government … they want to change the tenure of land, to drive out the present owners of the soil, and to put an end to ecclesiastical establishments [churches.]"

President Woodrow Wilson, who was intimately connected to conspiratorial power, once wrote:

"Some of the biggest men in the United States, in the fields of commerce and manufacture, are afraid of somebody, are afraid of something. They know there is a power somewhere so organized, so subtle, so watchful, so interlocked, so complete, so pervasive that they had better not speak above their breath when they speak in condemnation of it."

Former New York mayor John F. Hylan stated in 1922:

"The real menace of our Republic is the invisible government, which like a giant octopus sprawls its slimy length over our city, state, and nation ... At the head of this octopus are the Rockefeller—Standard Oil interests and a small group of powerful banking houses generally referred to as the international bankers [who] virtually run the U.S. government for their own selfish purposes."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was no stranger to secret societies, once said:

"In politics, nothing happens by accident. If it happens, you can bet it was planned that way."

Important figures from our history knew secret societies were secretly shaping world events. Did these clandestine groups simply vanish, or are their traditions carried on to this day?

For many, the term ‘secret society’ conjures up images of apron-wearing Freemasons or cloaked figures practicing ceremonial magick, but the clandestine fraternities of today have taken on a more modern appearance. This is exemplified by groups such as the Trilateral Commission, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR,) the elusive Bilderberg Group, and, of course, Klaus Schwab’s very public World Economic Forum.

For our purposes, we’ll be focusing specifically on the Council on Foreign Relations.

The Council on Foreign Relations

The council began as an outgrowth of a series of meetings conducted during World War I. Woodrow Wilson’s confidential advisor, Edward Mandell House had gathered roughly 100 of the most prominent men in the country at the time to discuss the postwar world. This group of foreign policy elite originally dubbed themselves “the Inquiry.” These men helped concoct Wilson’s famous ‘fourteen points,’ which he presented to Congress in January of 1918. The points could be seen as a globalist wish list, calling for the removal of "all economic barriers" between nations, "equality of trade conditions," and the formation of "a general association of nations."

House described himself as a Marxist socialist, yet his actions reflected the more subversive Fabian socialism.

He penned a novel several years prior called Philip Dru: Administrator. It’s claimed that he gave a copy of this work to Woodrow Wilson to read on a trip to Bermuda. In it, House describes a clandestine effort in the United States to establish the central bank, the graduated income tax, and the control of both political parties. Within two years of publication, two of these objectives, if not all three, had already been accomplished.

By late 1918, the stalemate on the Western Front, in addition to the entry of America into the war, forced Germany and the Central Powers to accept terms for peace, paving the way for the subsequent Paris Peace Conference of 1919, which led to the Treaty of Versailles.

Attending the Paris peace conferences were President Woodrow Wilson and his closest advisors, Colonel House, international bankers Paul Warburg and Bernard Baruch and almost two dozen members of ‘the Inquiry.’

The attendees embraced Wilson's plan for peace, including the formation of a League of Nations. However, under American law, the covenant had to be ratified by the U.S. Senate, which failed to do so, many senators being distrustful of a supranational organization.

Despite this setback, House met with both British and American peace conference delegates in Paris’s Majestic Hotel on May 30th and resolved to form an ‘Institute of International Affairs,’ with branches in both America and England. If they were to be denied their globalist League of Nations, then they would carry on their goals behind the scenes, away from public scrutiny.

The English branch became known as ‘the Royal Institute for International Affairs,’ known today as Chatham House. The US branch was incorporated on July 21st of that year as the Council on Foreign Relations, the name it still goes by today.

The Council’s primary funders included some of the world's most powerful individuals of the early 1900s.

Oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, who is arguably one of the most recognized men in American history, is alleged to have helped fund the organization. Other international bankers and financiers Paul Warburg, Jacob Schiff, Otto Kahn, and representatives of the family of J.P. Morgan rounded out the group’s backers.

Interestingly enough, these same funders all happened to have been intimately involved with both the panic of 1907 and the ensuing creation of the Federal Reserve.

The CFR’s founding president was J.P. Morgan Jr’s personal attorney, John W. Davis. Vice President Paul Cravath also represented Morgan properties. The council's first chairman was Russell Leffingwell, one of Morgan's partners and trustee of the Carnegie Corporation. Since most of the early CFR members had connections to Morgan, it’s been said that the council was heavily influenced by Morgan's interests.

The CFR played a key role in American policy during World War II and beyond. Journalist J. Anthony Lucas noted, "From 1945 well into the sixties, Council members were in the forefront of America's globalist activism."

According to the CFR’s own mission statement:

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, business executives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries.

But critics dispute this goal, noting that the CFR has had its hand in every major twentieth-century conflict. Some researchers believe the CFR is set on world domination through multinational business, international treaties and world government. Admiral Chester Ward, retired judge advocate general of the U.S. Navy and a longtime CFR member, was quoted as saying,

"The main purpose of the Council on Foreign Relations is promoting the disarmament of U.S. sovereignty and national independence and submergence into an all-powerful, one-world government."

He also went on to warn,

“The most powerful clique in these elitist groups have one objective in common—they want to bring about the surrender of the sovereignty and the national independence of the United States. A second clique of international members in the CFR … comprises the Wall Street international bankers and their key agents. Primarily, they want the world banking monopoly from whatever power ends up in the control of global government”

He detailed the CFR’s methods in a 1975 book coauthored with Phyllis Schlafly titled Kissinger on the Couch:

"Once the ruling members of the CFR have decided that the U.S. Government should adopt a particular policy, the very substantial research facilities of CFR are put to work to develop arguments, intellectual and emotional, to support the new policy, and to confound and discredit, intellectually and politically, any opposition …”

The inner workings of the CFR may be obscured from the public, but they produce a publication called ‘Foreign Affairs,’ which some believe is used to signal desired policies and future direction to those in power.

Even the Encyclopaedia Britannica admitted,

"Ideas put forward tentatively in this journal often, if well received by the Foreign Affairs community, appear later as U.S. government policy or legislation; prospective policies that fail this test usually disappear."

In effect, laws and government policies are not written by the people, but by the CFR for the benefit of the ruling class.

It is worth noting that every US Government administration since the Council’s inception has been packed with CFR members; the Clinton administration had over 100 Council members serving.

(Even Donald Trump’s administration wasn’t free of CFR influence.)

Gary Allen, whose book None Dare Call It Conspiracy sold more than five million copies despite being ignored by the establishment media, commented just before the 1972 national elections,

"There really was not a dime's worth of difference [between presidential candidates]. Voters were given the choice between CFR world government advocate Nixon and CFR world government advocate Humphrey. Only the rhetoric was changed to fool the public."

Allen echoed the dismay of many independent researchers of the time, who were suspicious of the CFR’s influence on our elections when he wrote,

"Democrats and Republicans must break the Insider control of their respective parties. The CFR-types and their flunkies and social climbing opportunist supporters must be invited to leave or else the Patriots must leave."

The CFR’s tentacles are not limited only to presidential cabinets, but reach deep into the intelligence community as well. Almost every CIA director since Allen Dulles has been a CFR member. Researchers have alleged that the CIA, in fact, serves as a security force, not just for corporate America, but for friends, relatives and fraternity brothers of the CFR.

This arrangement seems to serve as a two-way street. According to some researchers, the CFR has long been the CIA's principal constituency in the American public.

Article II of the CFR’s bylaws states that anyone revealing details of CFR meetings can be dropped from membership, thus qualifying the CFR as a secret society. This has caused the CFR to be the subject of a slew of conspiracies.

The CFR’s invitation-only membership, which was originally capped at 1,600 participants today numbers more than 5,000 of the most influential leaders in finance, commerce, communications and academia.

CFR Admission is an extremely discriminating and grueling process: candidates must be proposed by a current member, seconded by another member, approved by a committee, screened by a professional staff, and then, finally, must be approved by the Board of Directors.

The organization’s secrecy has been thoroughly protected by the western media. Journalist J. Anthony Lucas noted in 1971,

"Analysts of the Soviet press say the Council crops up more regularly in Pravda and Izvestia than it does in the New York Times …"

The CFR’s Board of Directors has historically been a who’s who of globalist financiers, establishment politicians, representatives of the military-industrial complex and heads of the world's largest corporations.

Current board members include BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, Emerson Collective founder and Ghislaine Maxwell confidant Laurene Powell Jobs and senior vice president and CFO of Alphabet and Google Ruth Porat, to name a few. The general CFR membership is composed of Wall Street types, international bankers, executives of powerful foundations, members of various think tanks and other tax-exempt foundations. There are also ambassadors, past and present presidents of the United States, secretaries of state, lobbyists, media conglomerate owners, university presidents and professors. Even federal and Supreme Court judges have joined the ranks, along with members of the military from both NATO and the Pentagon.

The running theme is power.

In addition to individual membership, the CFR also offers a corporate membership program, through which subscribing companies are provided a twice-a-year dinner briefing by government officials like the Treasury Secretary or the CIA director.

Some of the major corporate members include Apple, Bank of America, BlackRock, Chevron, Citi, ExxonMobil, Goldman Sachs, Google, Meta, PepsiCo, Nasdaq, and Morgan Stanley. This list is by no means comprehensive; in fact, it barely scratches the surface.

Though it is impossible to know the inner workings of the CFR, it is safe to say that the group’s influence is palpable.

Maybe the CFR is exactly what it claims to be, maybe it’s not.

Are these prestigious individuals merely part of some fancy club? Or are they the archetypal ‘men behind the curtain?’

When it comes to modern secret societies, our enduring uncertainty seems to be the only constant.